[ad_1]

Art accessibility has been a hot topic as of late, with many museums in the U.S. acknowledging the need to make more of an effort to connect with a wider range of audiences. It’s not that people don’t want to engage with art—they do—but rather that so much art is essentially locked away in institutions that are expensive to enter or have hours that conflict with the typical workday or have problematic histories some feel uncomfortable reckoning with.

Supporters of public art have long sought to remove these and other barriers that separate people from art, whether by putting masterpieces in commercial spaces, a la Larry Silverstein, or investing in public art, a la Jackson Hole, or mounting ambitious free exhibitions of important contemporary art in unexpected environments, a la Public Art Fund. That organization, in particular, has exhibited artworks by artists such as Ai Weiwei, Tatzu Nishi, Tauba Auerbach, Awol Erizku and Felix Gonzales Torres in busy urban environments like Moynihan Train Hall and Terminal B at LaGuardia Airport.

SEE ALSO: Artist Jesse Darling Wants Us to Think About What Hurts

In just a few days, Public Art Fund will unveil its latest project: their seventh solo artist exhibition with JCDecaux, a three-city show of photographic works by Clifford Prince King. If the name JCDecaux isn’t ringing any bells, that’s because it’s not a gallery or arts nonprofit but rather the largest outdoor advertising corporation in the world. “Clifford Prince King: Let me know when you get home,” a deeply personal and moving photo series, will open in New York, Chicago and Boston on 330 bus shelters and newsstands.

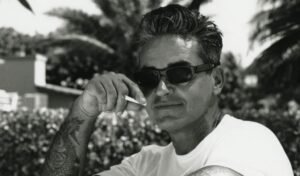

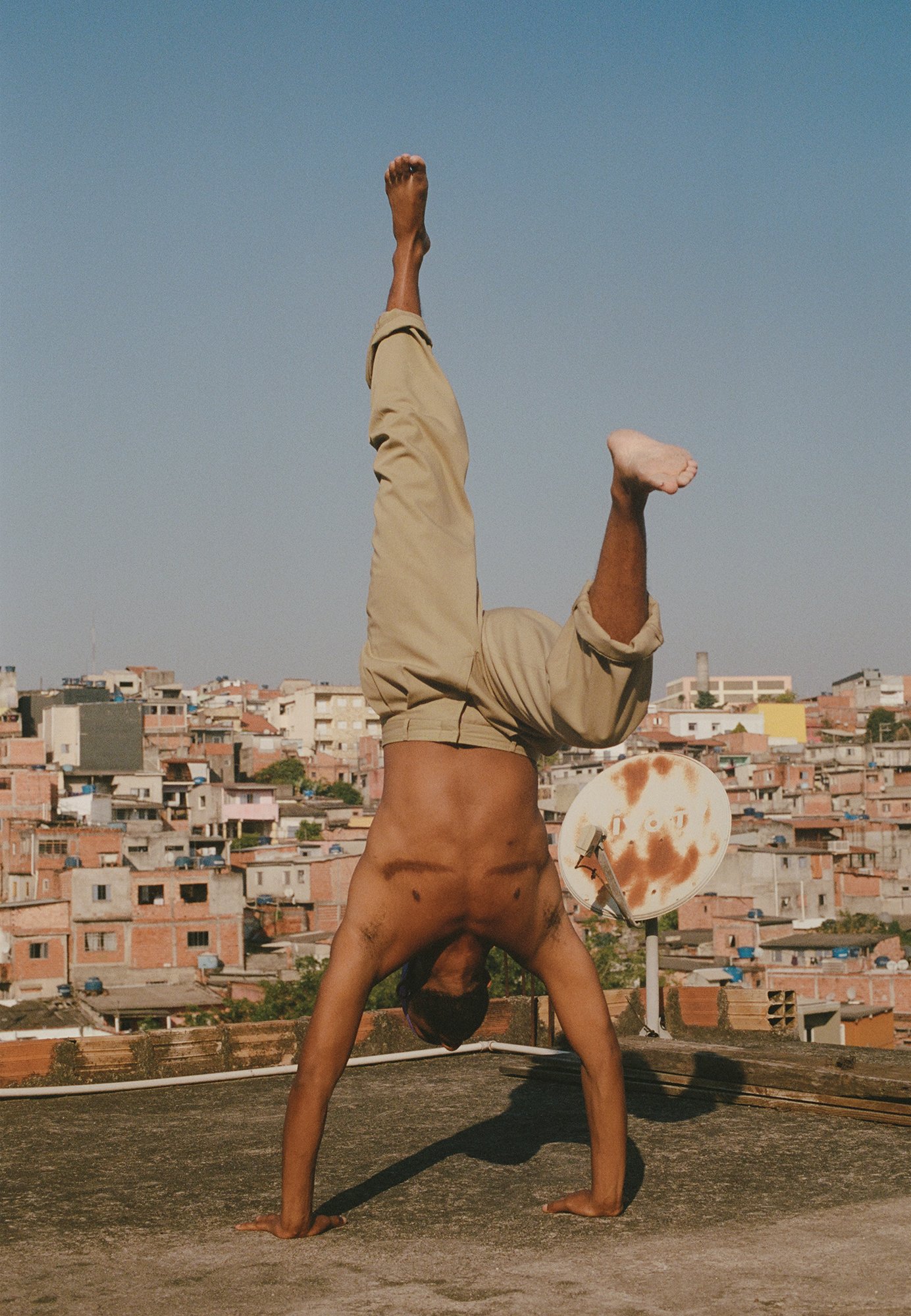

King, a self-taught photographer whose work is in the collections of the Hammer Museum, ICA Miami, Kleefeld Contemporary Art Museum, LACMA, the Minneapolis Institute of Art and the Studio Museum in Harlem, is largely known for his quietly beautiful depictions of Queer Blackness that capture tenderness and intimacy. Many of his photos hint at sexuality while overtly portraying psychological safety. They’re touching and poignant—looking at them, one can’t help but long for the feelings he captures.

The word that comes to mind is ‘connection,’ which is the overarching theme that has emerged in King’s practice. The thirteen photographs in “Let me know when you get home,” which was curated by Katerina Stathopoulou and is King’s first exhibition of public art, were taken during time he spent in São Paulo, Fire Island, Syracuse, Vermont and the Cayman Islands. Living nomadically, his approach to capturing connection seems very different—there’s still intimacy in the arresting larger-than-life portraits, but there’s a longing in the visual diary of his travels, too.

Observer recently had the opportunity to ask King about putting his photography in front of such a large audience, the relationships at the heart of his work and what he’ll be focusing on next.

How does “Let me know when you get home” differ from your previous work?

Most of my work beforehand was made in my home(s) in Los Angeles, often indoors or in my sitter’s spaces. A large portion of my practice focused on interior space and privacy. With this body of work, I’m not stationary. I was moving around a lot these couple of months and started documenting the changing environments and people I came across along the way.

What was it like to live and work nomadically? Did you learn anything new about yourself or your practice?

I did something similar in my early twenties, but this time around felt different leaning into my thirties. I enjoy being on the road. Typically, I have a place to return to once it’s all over. This time, I put all my things in storage in L.A., so it felt like there wasn’t a designated place to go back to. Some waves of sadness, but I think ultimately those were moments of growth into the next phase of my personhood. I learned that my idea of home was shaped around items, objects and familiarity which I still find semi-true, but my relationship with that feels different now.

Your images are autobiographical and personal but will be displayed very publicly in this case—does that feel fraught? More risky than putting your work in a museum?

Surprisingly, not at all! I released that anxiety a while ago; sharing my images online and in various other ways has liberated that nervous feeling. I think more of my frightfulness comes from speaking about the work or having to explain myself.

Relationships are at the heart of all your work—why have you chosen to focus so intentionally on connections?

I was (and still am) a shy person in social settings. Photography helped me come out of my shell and approach people in a way that I’ve always wanted to. I have this strong desire to connect with people, especially when I’m somewhere I’ve never been. It often manifests as people watching and hopefully will lead to a nice conversation and learning experience.

On March 12th, we’re hosting a hot chocolate stand in Bushwick by one of the two bus shelters showcasing the works on Dekalb Avenue, in hopes of connecting with the community and having the opportunity to make light conversation with people going about their day in the neighborhood.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but my understanding is that one of your past goals has been to capture the beauty of Queer Blackness, challenging stereotypes. How do you see your work evolving in the future as the world changes?

I’m not sure that my goal is to challenge, but more to provide an alternative depiction of what my life and other’s lives might look like. I think I see beauty in people and places that aren’t obvious; within details, moments of sunlight and mannerisms. As the world changes, I will also change; I guess I’m leaning more toward specific areas of interest, versus the fundamental idea of Black Queer existence. Moving forward, my work will foremost reflect where I’m at mentally, and geographically and will depend on the resources and support that I’m offered.

Public Art Fund Talks: Clifford Prince King with Lyle Ashton Harris will take place at The Cooper Union Frederick P. Rose Auditorium on February 27 at 6:00 p.m. Register here. Hot Cocoa On-the-Go with Clifford Prince King will take place by the two bus stops on Dekalb Ave near Maria Hernandez Park in Bushwick, Brooklyn, on March 12 from 3:00 to 4:30 p.m.

[ad_2]

Source link